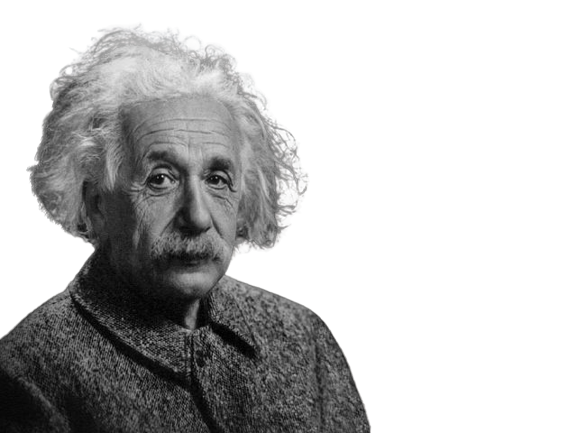

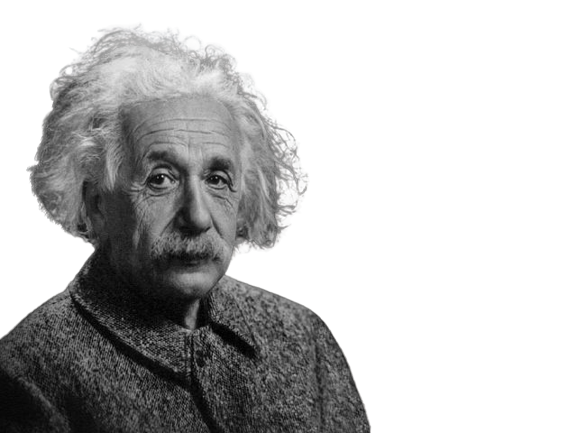

Albert Einstein, (born March 14, 1879, Ulm, Württemberg, Germany—died April 18, 1955, Princeton, New Jersey, U.S.), German-born physicist who developed the special and general theories of relativity and won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1921 for his explanation of the photoelectric effect. Einstein is generally considered the most influential physicist of the 20th century.

Einstein’s parents were secular, middle-class Jews. His father, Hermann Einstein, was originally

a featherbed salesman and later ran an electrochemical factory with moderate success. His

mother, the former Pauline Koch, ran the family household. He had one sister, Maria (who went by

the name Maja), born two years after Albert.

Einstein would write that two “wonders” deeply affected his early years. The first was his

encounter with a compass at age five. He was mystified that invisible forces could deflect the

needle. This would lead to a lifelong fascination with invisible forces. The second wonder came

at age 12 when he discovered a book of geometry, which he devoured, calling it his “sacred

little geometry book.”

Einstein became deeply religious at age 12, even composing several songs in praise of God and

chanting religious songs on the way to school. This began to change, however, after he read

science books that contradicted his religious beliefs. This challenge to established authority

left a deep and lasting impression. At the Luitpold Gymnasium, Einstein often felt out of place

and victimized by a Prussian-style educational system that seemed to stifle originality and

creativity. One teacher even told him that he would never amount to anything.

Yet another important influence on Einstein was a young medical student, Max Talmud (later Max

Talmey), who often had dinner at the Einstein home. Talmud became an informal tutor, introducing

Einstein to higher mathematics and philosophy. A pivotal turning point occurred when Einstein

was 16 years old. Talmud had earlier introduced him to a children’s science series by Aaron

Bernstein, Naturwissenschaftliche Volksbucher (1867–68; Popular Books on Physical Science), in

which the author imagined riding alongside electricity that was traveling inside a telegraph

wire. Einstein then asked himself the question that would dominate his thinking for the next 10

years: What would a light beam look like if you could run alongside it? If light were a wave,

then the light beam should appear stationary, like a frozen wave. Even as a child, though, he

knew that stationary light waves had never been seen, so there was a paradox. Einstein also

wrote his first “scientific paper” at that time (“The Investigation of the State of Aether in

Magnetic Fields”).

After graduation in 1900, Einstein faced one of the greatest crises in his life. Because he

studied advanced subjects on his own, he often cut classes; this earned him the animosity of

some professors, especially Heinrich Weber. Unfortunately, Einstein asked Weber for a letter of

recommendation. Einstein was subsequently turned down for every academic position that he

applied to. He later wrote,

"I would have found [a job] long ago if Weber had not played a dishonest game with me."

Meanwhile, Einstein’s relationship with Maric deepened, but his parents vehemently opposed the

relationship. His mother especially objected to her Serbian background (Maric’s family was

Eastern Orthodox Christian). Einstein defied his parents, however, and in January 1902 he and

Maric even had a child, Lieserl, whose fate is unknown. (It is commonly thought that she died of

scarlet fever or was given up for adoption.)

In 1902 Einstein reached perhaps the lowest point in his life. He could not marry Maric and

support a family without a job, and his father’s business went bankrupt. Desperate and

unemployed, Einstein took lowly jobs tutoring children, but he was fired from even these jobs.

The turning point came later that year, when the father of his lifelong friend Marcel Grossmann

was able to recommend him for a position as a clerk in the Swiss patent office in Bern. About

then, Einstein’s father became seriously ill and, just before he died, gave his blessing for his

son to marry Maric. For years, Einstein would experience enormous sadness remembering that his

father had died thinking him a failure.

With a small but steady income for the first time, Einstein felt confident enough to marry

Maric, which he did on January 6, 1903. Their children, Hans Albert and Eduard, were born in

Bern in 1904 and 1910, respectively. In hindsight, Einstein’s job at the patent office was a

blessing. He would quickly finish analyzing patent applications, leaving him time to daydream

about the vision that had obsessed him since he was 16: What would happen if you raced alongside

a light beam? While at the polytechnic school he had studied Maxwell’s equations, which describe

the nature of light, and discovered a fact unknown to James Clerk Maxwell himself—namely, that

the speed of light remains the same no matter how fast one moves. This violates Newton’s laws of

motion, however, because there is no absolute velocity in Isaac Newton’s theory. This insight

led Einstein to formulate the principle of relativity: “the speed of light is a constant in any

inertial frame (constantly moving frame).”

Albert Einstein’s time on earth ended on April 18, 1955, at the Princeton Hospital. In April of

1955, shortly after Einstein’s death, a pathologist removed his brain without the permission of

his family, and stored it in formaldehyde until around 2007, shortly before dying himself. In

that time, the brain of the man who has been credited with the some of the most beautiful and

imaginative ideas in all of science was photographed, fragmented—small sections parceled to

various researchers. His eyes were given to his ophthalmologist. These indignities in the name

of science netted several so-called findings—that the inferior parietal lobe, the part said to

be responsible for mathematical reasoning was wider, that the unique makeup of the Sulvian

fissure could have allowed more neurons to make connections. And yet, there remains the sense

that no differences can truly account for the cognitive abilities that made his genius so

striking.

One might expect a story of encroaching death, however restrained, to chronicle confusion and

fear. Medically supported death was a regular occurrence by the middle of the 20th century, and

Einstein died in his local hospital. But what is immediately striking from the account is the

simplicity and calmness with which Einstein met his own passing, which he regarded as a natural

event. The telling of this chapter is matter of fact, from his collapse at home, to his

diagnosis with a hemorrhage, to his reluctant trip to the hospital and refusal of a famous heart

surgeon. Dukas writes that he endured the pain from an internal hemorrhage (“the worst pain one

can have”) with a smile, occasionally taking morphine. On his final day, during a respite from

pain, he read the paper and talked about politics and scientific matters. “You’re really

hysterical—I have to pass on sometime, and it doesn’t really matter when.” he tells Dukas, when

she rises in the night to check on him.

Einstein refrigerator

In 1926, Einstein and his former student Leo Szilard patented a refrigerator design that used no moving parts and relied on the properties of gases to cool a system.

Einstein-Szilard letter

In 1939, Einstein co-authored a letter to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, warning him of the potential for Nazi Germany to develop nuclear weapons and urging the U.S. to pursue its own nuclear research.

Nuclear chain reaction

Einstein's famous equation, E=mc², provided the theoretical framework for nuclear fission, which can create a chain reaction that releases a tremendous amount of energy.

Theory of relativity

Einstein's theory of relativity, which he developed in the early 20th century, revolutionized our understanding of space, time, and gravity.

Photon theory of light

Einstein proposed that light was made up of individual particles, or photons, which helped to explain the behavior of light in certain situations.

Brownian motion

Einstein's study of the random motion of particles in a fluid, known as Brownian motion, helped to confirm the existence of atoms and molecules.

Unified field theory

Einstein spent much of the latter part of his life searching for a "theory of everything" that would unify all of the forces of nature into a single framework.

Bose-Einstein condensate

Einstein's work on the behavior of atoms at extremely low temperatures laid the groundwork for the discovery of the Bose-Einstein condensate, a new state of matter.

Critical opalescence

Einstein helped to explain the phenomenon of critical opalescence, which occurs when certain fluids near a critical point become turbid and opaque.

Gravitational waves

Einstein's theory of general relativity predicted the existence of gravitational waves, which were finally observed in 2015 by the LIGO experiment.